Electrical maintenance in cooling infrastructure differs significantly from standard electrical work. Water, humidity, mist, and condensation create an environment that actively degrades components and amplifies conductivity. These factors transform routine tasks into high-stakes operations where a minor oversight can lead to severe injury or equipment failure.

Cooling system electrical safety requires a specialized approach because the equipment operates at the intersection of high-voltage power and corrosive, wet conditions. Unlike a climate-controlled electrical room, a cooling tower or pump station exposes insulation, terminals, and enclosures to chemical vapors and moisture. This accelerates corrosion and compromises the integrity of protective barriers.

This guide focuses specifically on the electrical risks inherent to cooling systems and the controls necessary to mitigate them. Understanding where electrical hazards hide in these mechanical spaces remains the first step toward effective prevention.

Table of Contents

ToggleElectrical Components Commonly Serviced in Cooling Systems

Technicians must first identify the specific equipment that presents electrical risks within the cooling loop. These components often sit in direct contact with water or operate in high-humidity zones.

- Motors and Fan Drives: Large induction motors drive the fans responsible for heat rejection. These units often operate at high voltages and are subject to vibration and moisture ingress.

- Pumps and Auxiliary Equipment: Circulation pumps move water through the system. Their electrical connections are frequently located in pits or low-lying areas where water accumulation occurs.

- VFDs and MCC Panels: Variable Frequency Drives (VFDs) and Motor Control Centers (MCCs) regulate speed and power. These cabinets contain high-energy circuits and sensitive control electronics that are vulnerable to environmental contamination.

- Sensors, Control Panels, and Automation Systems: While often lower voltage, these systems interface with higher power circuits. Faults here can bypass safety interlocks or energize equipment unexpectedly.

Pre-Maintenance Electrical Risk Evaluation

Standard risk assessments often fail to account for the dynamic nature of cooling environments. Effective preparation involves verifying the current state of the system against engineering documentation before any tool touches a cabinet.

- Reviewing Single-Line Diagrams: Technicians must consult up-to-date diagrams to understand feed sources. This ensures no back-feed loops exist from auxiliary generators or bypass circuits.

- Identifying Live vs. Potentially Energized Components: Workers must distinguish between components that are normally energized and those that may retain a charge, such as capacitors in VFDs.

- Environmental Risk Checks: The evaluation must include a scan for standing water, active condensation, or severe corrosion on enclosures. These factors dictate whether standard isolation procedures are sufficient or if additional barriers are necessary.

- Determining Required Isolation Level: Based on the environmental scan, the team determines if simple switching is enough or if racking out breakers is required to ensure a physical air gap.

Lockout-Tagout for Cooling System Electrical Circuits

Effective isolation prevents the unexpected release of hazardous energy during maintenance. Implementing lockout-tagout protocols specifically for cooling applications ensures that both power and control sources are neutralized.

- Electrical Isolation Points: Identify the primary disconnect for the specific piece of equipment. In cooling systems, this disconnect may be remote from the motor or pump it serves.

- Control Circuits vs. Power Circuits: Locking out the main power does not always de-energize control voltage. Technicians must verify that interlock wiring and external control feeds are also isolated.

- LOTO Sequencing for Motors, VFDs, and Control Panels: Follow a strict sequence to shut down equipment. Stop the VFD via the keypad before opening the line contactor to prevent arcing and component damage.

- Verification of Isolation Before Work: The process is not complete until the technician attempts to start the equipment and verifies zero energy. This step confirms that the correct disconnect was opened and that the device is truly inoperable.

Arc Flash Risk Management in Cooling System Maintenance

Moisture and corrosion can lower the impedance of air gaps, increasing the likelihood of an arc flash event. Specialized arc flash protection strategies are essential when working near energized cooling equipment.

- Why Arc Flash Risk Increases: Conductive dust and humidity in mechanical rooms can create tracking paths across insulators. This instability makes the initiation of an arc more probable during switching or testing.

- Panel Labeling and Incident Energy Awareness: Every panel must bear a label stating the incident energy level. Technicians must read these labels to determine the required level of protection before approaching.

- Arc Flash Boundaries in Mechanical Rooms: Physical boundaries must be established to keep unqualified personnel away. In cramped mechanical rooms, these boundaries often extend into walkways, requiring temporary barriers.

- When Energized Work Should Never Be Permitted: If water ingress is visible or if the enclosure is compromised by rust, energized work is strictly prohibited. The risk of a fault propagating is too high in these conditions.

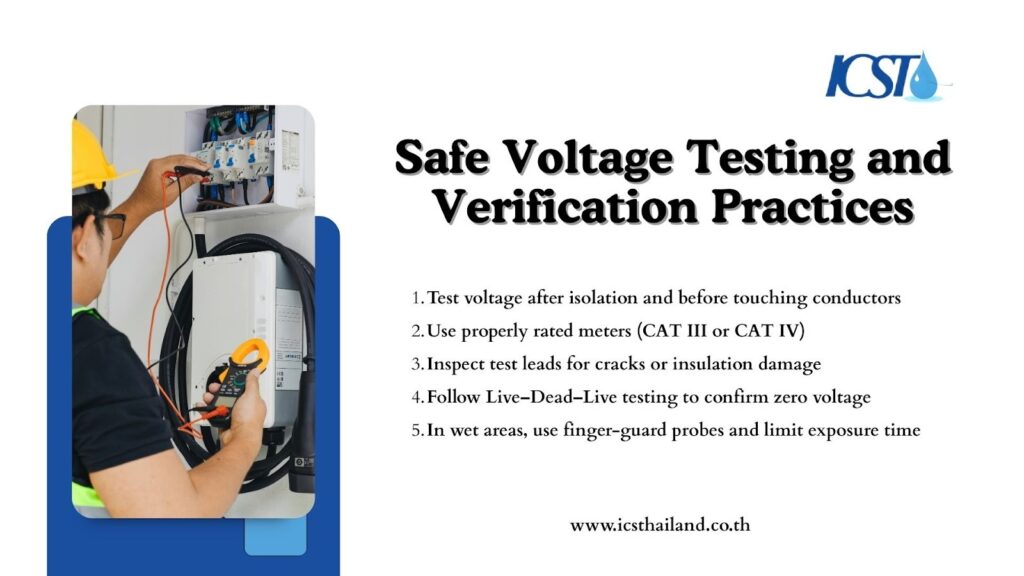

Safe Voltage Testing and Verification Practices

Never assume a circuit is de-energized. Assuming a circuit is dead without verification is a leading cause of electrical shock and arc flash fatalities. Rigorous voltage testing using approved and properly rated equipment is the only definitive way to confirm that an electrically safe work condition has been established.

This critical step protects workers from unforeseen hazards and ensures compliance with safety regulations.

- When Voltage Testing is Required: Testing occurs immediately after isolation and before touching any conductor. It also applies when troubleshooting control circuits where live voltage is expected.

- Approved Testing Tools and Ratings: Use meters rated for the specific category of the environment (typically CAT III or CAT IV). Verify that the leads are free of cracks and insulation damage.

- Live–Dead–Live Testing Method: Test the meter on a known live source to verify functionality. Test the target circuit to confirm zero voltage. Test the meter on the known source again to ensure it did not fail during the process.

- Testing in Wet or High-Humidity Environments: If the area is wet, use probes with finger guards and minimize the time the enclosure is open. Moisture on test leads can create a conductive path to the technician.

Grounding and Bonding in Cooling System Equipment

A robust grounding system provides a safe path for fault current, ensuring that protective devices trip quickly. In cooling systems, corrosion attacks these connections, compromising their effectiveness.

- Importance of Equipment Grounding Continuity: The ground wire ensures that the metal case of a motor does not become energized during a fault. Regular checks must verify that this connection remains low resistance.

- Bonding of Motors, Frames, and Metallic Piping: All metallic components within the system must be bonded together to create an equipotential zone. This prevents dangerous voltage differences between simultaneous touch points.

- Ground Fault Risks in Cooling Towers and Basins: Immersion heaters and basin level sensors are prone to ground faults. Dedicated ground fault circuit interrupters (GFCIs) or ground fault protection relays are critical here.

- Inspection of Grounding Connections During Maintenance: Visually inspect ground lugs for green copper corrosion or loose terminations. A corroded ground is an open circuit waiting to cause an injury.

Electrical PPE for Cooling System Maintenance Tasks

Personal Protective Equipment (PPE) serves as the last line of defense against electrical hazards. The wet nature of cooling environments necessitates specific gear choices to ensure worker safety.

- Arc-Rated Clothing Requirements: Personnel must wear flame-resistant (FR) clothing that meets the arc rating specified on the equipment label. Synthetic fibers that melt are prohibited.

- Insulated Gloves and Hand Tools: Rubber insulating gloves with leather protectors are mandatory when working within the restricted approach boundary. Voltage-rated hand tools prevent accidental bridging of phases.

- Face and Eye Protection for Electrical Exposure: An arc-rated face shield protects against the intense heat and molten metal shrapnel generated during an arc flash. Safety glasses are worn underneath the shield.

- Footwear Considerations in Wet Locations: Dielectric boots or overshoes provide secondary protection against step potential. Standard leather boots absorb water and lose their insulating properties in wet mechanical rooms.

Role of Qualified Personnel in Electrical Cooling System Work

Regulations distinguish clearly between a general maintenance worker and a “qualified person” regarding electrical tasks. This distinction dictates who is legally and safely permitted to interact with exposed energized conductors.

- What Defines a “Qualified Person”: A qualified person possesses the skills and knowledge related to the construction and operation of the electrical equipment and has received safety training to recognize and avoid the hazards involved.

- Electrical Competency vs. Mechanical Competency: A skilled pipefitter is not automatically qualified to troubleshoot a VFD. Competency is task-specific and must be verified through training records.

- Supervision Requirements for Mixed-Skill Tasks: When unqualified personnel must work near exposed electrical hazards, a qualified person must supervise them to ensure they remain outside the approach boundaries.

- Contractor Qualification Verification: Facility managers must verify that external electrical contractors hold the necessary licenses and safety certifications before allowing them access to cooling infrastructure.

Conclusion

Ensuring electrical safety in cooling systems is an ongoing process that demands proper evaluation, discipline, and adherence to best practices. Key measures include implementing robust lockout/tagout procedures, using appropriate arc flash protection, and relying on qualified professionals to handle maintenance.

The combination of electricity and water introduces unique hazards, making it crucial to prioritize cooling system electrical safety to protect personnel and maintain the reliability of critical infrastructure. By taking these proactive steps, facilities can reduce risks and enhance overall system performance.

For comprehensive cooling system maintenance and expert support, visit the ICST website. Our team is dedicated to helping you maintain a safe and efficient operation for your cooling systems while safeguarding your most valuable assets, your people.

Frequently Asked Questions

What is cooling system electrical safety?

Cooling system electrical safety refers to the specific practices and protocols used to mitigate electrical hazards in the wet, corrosive environments typical of cooling towers and pump rooms. It involves specialized risk assessments, moisture control, and strict isolation procedures.

Why is lockout-tagout critical in cooling system maintenance?

Lockout-tagout is critical because it ensures that equipment is completely de-energized and cannot be restarted accidentally during maintenance. In cooling systems, this prevents electrocution from power circuits and unexpected movement from automated control systems.

What electrical hazards are common in cooling towers?

Common hazards include short circuits caused by water ingress, corrosion of grounding connections, and electric shock from high-humidity environments. Arc flash incidents are also a significant risk due to the potential for tracking across damp insulation.

Who is qualified to perform electrical work on cooling systems?

Only “qualified personnel” who have received specific training on the construction, operation, and hazards of the electrical equipment are permitted to perform electrical work. General mechanical technicians are not qualified to work on exposed energized circuits.